When Network Rail published version 2.0 of its Footbridges & Subways Design Manual in June, there was a significant addition to its catalogue of approved standard designs – the AVA bridge, the first of which is set to be installed at Stowmarket station in May 2025 by Walker Construction.

The question of footbridge design was one of Anthony Dewar’s first priorities when he was appointed Network Rail’s professional head of buildings and architecture in 2017. Network Rail’s Access for All programme was set on providing obstacle-free, accessible routes to and between platforms. In some places this can be provided by subways, but more often it means a footbridge over the tracks, serviced on each side by a passenger lift.

With the traditional 400-Series bridge design incompatible with lifts, this has required a programme of bridge replacements at an approximate rate of 20 a year.

Network Rail owns more than 1,500 station footbridges, and a further 900 in out-of-station settings. It needs to be replacing 200 a year, not 20.

To help speed up the programme and reduce costs, Dewar’s team set about producing a catalogue of standard designs, working on several fronts simultaneously.

In June 2018 a RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) design competition was launched – the first that Network Rail had held for a generation. It attracted 121 submissions from architects and engineers around the world. In December 2018 the winner was named as The Framing Bridge (now known simply as Frame), designed by Gottlieb Paludan Architects from Denmark with Strasky Husty & Partners from the Czech Republic.

“Frame was the winner of the design competition,” Dewar explains, “but we wanted a catalogue. So at the same time as the design competition we ran tenders – one through an engineering consultancy framework and one through an architectural framework.”

Out of this process came two more designs for station footbridges, the Ribbon and the Beacon as well as a new fibre reinforced polymer (FRP) option for non-station environments, called Flow.

By 2020 Network Rail was able to produce the first edition of the Footbridges & Subways Design Manual, explaining how to choose and use the standard designs that had now been made available to purchasers across Network Rail’s five regions.

While this was seen as a significant step forward, there was impatience to move faster. In many ways Network Rail engineering had been stuck in the past, with standard designs only available as a pdf file rather than CAD.

In the same year that the first edition of the manual was produced, Network Rail secured funding for a research & development project for a new concept footbridge.

Co-funded by Network Rail and the TIES (Transport Infrastructure Efficiency Strategy) Living Lab programme, the so-called AVA project was backed a grant from Innovate UK through its Transforming Construction programme, plus contributions from the Department for Transport, HS2, Transport for London, Network Rail and Highways England.

Dewar put together a consortium comprising contractor Walker Construction, structural engineer Expedition Engineering and architect Hawkins/Brown with specific directions: apply modern methods of construction to maximise off-site manufacturing and preassembly to minimise temporary station works, saving both time and money.

Maintenance requirements and carbon implications also had to be part of the equation to minimise whole life costs and climate impact.

Hawkins/Brown had been highly commended in the RIBA design competition proposing a modular ‘kit of parts’ that would enable a standardised bridge system to be adapted to different contexts via the use of simple pre-fabricated, clip-on modular elements. The addition of Expedition Engineering’s brains and Walker Construction’s specialist knowledge of building things next to, and over, railways, meant that the AVA consortium could pick up and run with what the architects had started.

The AVA project was temporarily derailed by a couple of speed bumps. Firstly there was the covid pandemic; and then the original steelwork fabricator that had built the prototype in Market Harborough went out of business. In 2022 the prototype was disassembled and moved to Sittingbourne in north Kent, where it was reassembled in the yard of replacement steel fabricator McNealy Brown. It then transpired that the original steelwork contractor did not have the depth of experience in structures that had previously been thought and the lengthy structural certification process had to be re-started.

As a consequence it was a full two years after the AVA prototype had arrived in Sittingbourne that it could finally be unveiled to the public through a series of events in July this year, a month after publication of Version 2.0 of the Footbridges & Subways Design Manual that set out the details of the design thus:

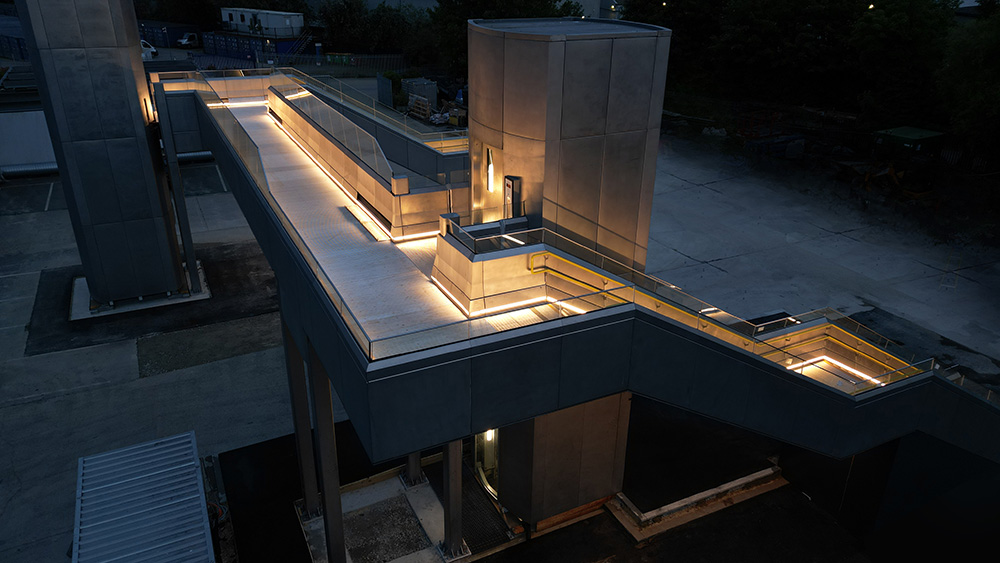

“AVA differs from other bridge designs as the external cladding and the structural elements behind the cladding are all made of stainless steel. The limited need for maintenance is clear in the appearance of the bridge, and the bridge becomes an object with a very strong identity. With its fixed choice of materials, the bridge is an almost high tech design statement. The bridge design is developed in a close collaboration between Network Rail, the contractor and the architect in an effort to create a design which is easy to construct. This is expressed in a high degree of modularity, reducing building costs. The AVA footbridge design does not yet have a standard Network Rail design status but is an emerging design.”

The AVA bridge was scheduled to make its debut at Stowmarket station in Suffolk back in March 2023. This has now slipped to May 2025, with Walker Construction on a £4.5m contract to deliver and install.

Phil Webb, managing director of Walker Construction, says that one of the biggest benefits of the AVA bridge is its speed of installation, saving time and money: it only needs a 36-hour line possession to install, which is roughly half the standard industry procedure, and there is a target to get this down to 27 hours with a bit more work. Total time required on site – for preparations, assembly and foundations – is put at 15 weeks and contract award to handover (all other things being equal) should be 20 months, both of which are also less than half the time taken by current standard industry practice.

AVA is not just cheaper to install but also cheaper to look after. Being bead-blasted stainless steel, it needs no painting or repainting. The structure has a 120-year design life while the aluminium deck has a 60-year design life and 25-year warranty.

Another significant feature of the AVA bridge is its passenger lifts.

Phil Webb reveals that the major lift manufacturers were all approached but none was particularly interested in getting involved in the project. So they went the boutique option and brought in Sheffield-based mechanical handling specialist ARX, part of Kinetic Solutions Group. What ARX has come up with is a system designed specifically for railway station environments. A complete lift module, including car and shaft, arrives on the back of a lorry, ready assembled and fully tested. It is then lifted into place, bolted down and clad in steel. Maintenance work can be carried out at station platform level by opening a hatch at the back.

In fact, ARX’s first-of-its-kind modular lift will be making its solo debut next April, without the AVA footbridge, at Seven Sisters underground station in London.

Webb says that for all the benefits of AVA, it could be even cheaper. As with all things factory-made, the real benefits come from volume. Network Rail knows that it needs hundreds of new footbridges with lift systems but is not in a position to place bulk orders. This is largely due to funding constraints but the structure of the industry does not help. Network Rail has five regions and each manages its own purchasing. If they could only centralise purchasing, Webb says, and order six or seven bridges at the same time, then the AVA consortium could really show the efficiency of its manufacturing-led approach.

It is the concept of manufacturing rather than traditional fabrication that is the core of the AVA concept.

“The AVA bridge project was originally called the Model T project but we were not allowed to call it that because it is still a brand name,” Anthony Dewar recalls.

“We are aiming for Industry 4.0. We are probably at between 2.0 and 3.0 now and able with AVA to get to 4.0.”

Dewar sounds moderately relaxed about (or possibly resigned to) the rate of progress with his new bridge designs seeing the light of day. Two modified Ribbon footbridges have been built in Scotland, at Reston Station and East Linton Station. The first Beacon bridge was lifted in to place at Garforth station, Leeds, in April this year at a cost of £6m but it took until the end of July before it was finally completed and, even then, the lifts had yet to be installed at that point. (Garforth station’s previous Grade II listed bridge has been relocated to the Bredgar & Wormshill Light Railway in Kent.)

In non-station settings, the prototype Flow bridge was installed in January 2023 in a rural setting to replace a pedestrian level crossing, just north of Craven Arms in the Shropshire hills. Another is planned for 2025.

“The incubation period for a footbridge can be three or four years,” Dewar says. “Part of that is down to the complicated stakeholder network with local authorities and train operating companies.”

Why AVA?

Chris Wise, a senior director with Expedition Engineering, explains why AVA was chosen as the name of the new bridge design:

“The AVA footbridge and lift system is manufactured from two stable ends (the two A’s), with a spanning element (the V). The name was therefore chosen because the ‘V’ slots directly into the space between the two ‘A’s’, and the letters have the same connecting geometry.

“It is also prismatic, echoing the folded plate language of the bridge monocoque.

“And lastly the name Ava, being a primarily a female name, means: ‘to breathe, to live’”.

Network Rail’s Footbridges & Subways Design Manual was republished in June 2024 with four standard types for station environments – Beacon, Ribbon, Frame, AVA – plus two others for non-station environments: 400-series and Flow. AVA and Flow are new entries to the 2024 edition.

National Rail has also developed an augmented reality tool to test standard bridges in specific environments. It is possible to download an app with the tool to your mobile phone. The app, called “Arki”, allows you to point to a desired standard bridge, and via the camera on your mobile phone, place it over a selected location. The 3D model of the bridge can be rotated, scaled and positioned so that it eventually looks as if it has been built in reality.

Station settings:

Frame

This footbridge design by Gottlieb Paludan Architects and Davies Maguire was the winner of Network Rail’s 2018 RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) footbridge competition. The roof and deck are structurally independent. The roof structures are concealed by metal cladding. The modular design facilitates a variety of configurations. There have been no buyers of this bridge yet.

Ribbon

The generic design of this bridge is by Knight Architects and Arup. The key design innovation is a 30-degree rotation of the lift shaft, which improves visibility and natural wayfinding. This requires a slightly wider platform by the stairs, but the length of the stair block is short due to the bend of the third flight of steps. The overall form is organic and continuous without emphasis on individual elements of the structure. Local variations are restricted to the choice of cladding for the lift towers and the lift motor rooms below the stairs.

Two modified Ribbon footbridges have been built in Scotland at Reston Station and East Linton Station.

Beacon

First bridge is at Garforth Station near Leeds. The generic design is by Haskoll and Davies Maguire. The Beacon design is characterised by a high degree of enclosure and transparency. It is aimed primarily at smaller local and commuter stations. The lift towers supporting the minimal steel structure are emphasised and illuminated internally as beacons. Local variations are restricted to the choice of cladding for the lift towers and the lift motor rooms below the stairs.

Ava

The generic design is by Hawkins/Brown and Expedition Engineering, which have formed the Ava consortium together with contractor Network Rail, Walker Construction, McNealy Brown (steelworks) and ARX (lift system). The first AVA bridge is set to go into Stowmarket station in May 2025. The first lifts will be used in Seven Sisters station in April 2025.

Non-Station settings:

400-series

This traditional Network Rail design has been built in numerous stations across the UK – a straightforward, robust, painted steel structure. Unlike the station designs, there are no lift options and no roof covering possible. On this basis it is no longer considered suitable for station settings and thus is suggested only for non-station environments. The bridge pictured is in Wymington, near Bedford, from the Network Rail design manual.

Flow

Flow stands for fibre-reinforced polymer (FRP), lower cost, optimised design, working bridge.

It is designed by Knight Architects and Jacobs for non-station settings. The prototype was installed in January 2023 in a rural setting to replace a pedestrian level crossing, just north of Craven Arms in the Shropshire hills.

Another Flow footbridge with lifts is planned to open in 2025.

And the one that got away:

Futura

This is a notable omissions from the manual.

In 2020 Network Rail announced that it had teamed up with the National Composites Centre (NCC) to realise a footbridge submitted to its design competition by Marks Barfield Architects and consulting engineer Cowi. The Futura comprised a kit of parts with large factory-moulded fibre reinforced polymer (FRP) structural components complemented by glass/steel enclosure.

Hopes were high but Anthony Dewar, Network Rail’s professional head of buildings and architecture in 2017, reveals: “We undertook further development of the Futura with the NCC/Cowi after the footbridge competition at the same time as developing the Beacon, Ribbon and Frame but decided to pause this work as we noted a number of significant technical challenges with FRP materials needed to overcome – e.g. fire/smoke performance, demonstration of the materials sustainability, cost, structural performance etc – and focus our resources on one type of FRP bridge, the Flow, to overcome these challenges.